Alexander Gardner & Henry De Witt Moulton

Rays of Sunlight from South America, 1865

Photo album; Albumen prints (68)

Each 6 3/4 x 8 1/2 inches; mounts larger

With printed captions and credits on recto.

Lacking front cover, introductory text, and first two plates.

With printed captions and credits on recto.

Lacking front cover, introductory text, and first two plates.

Sold

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

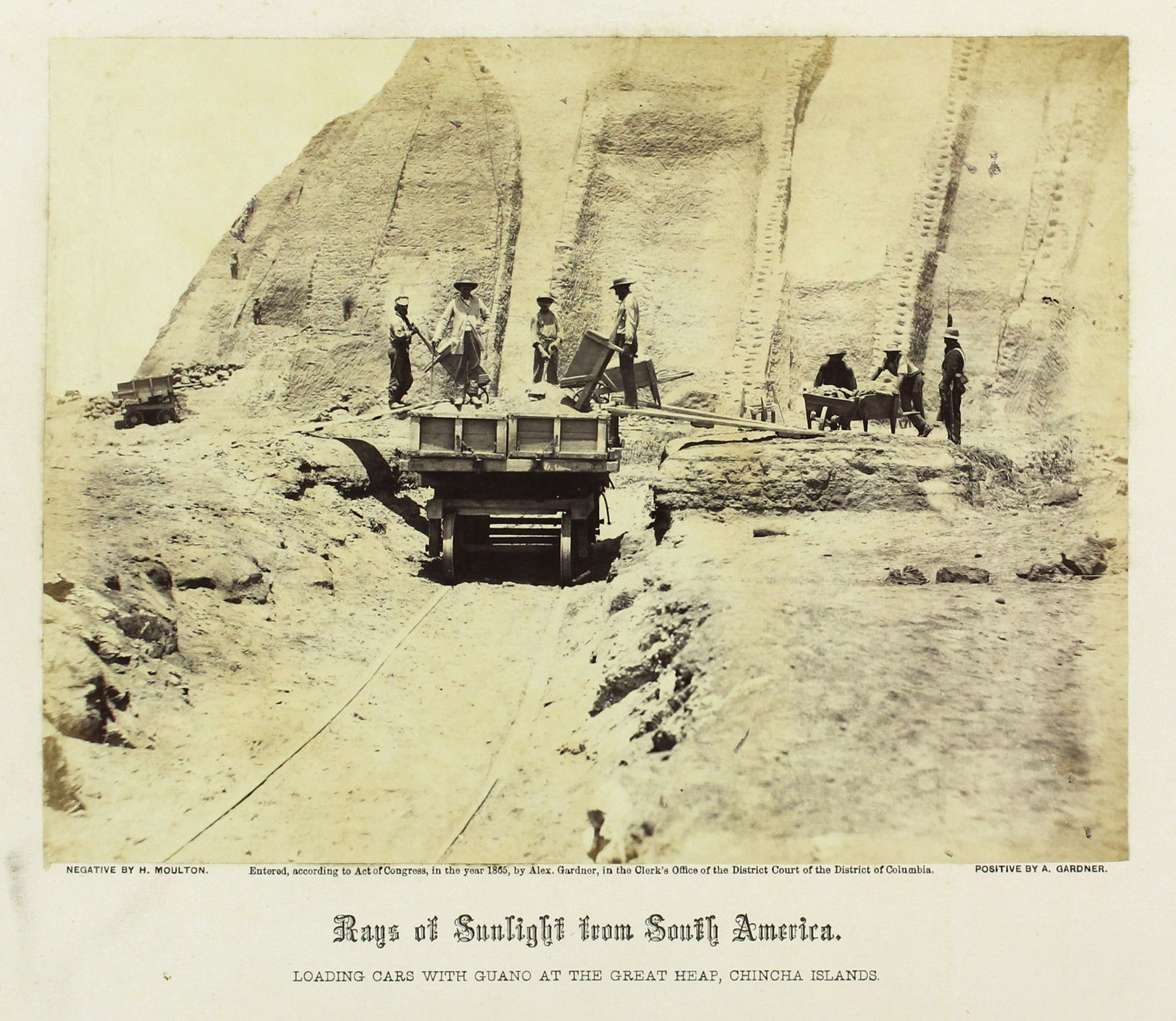

Monumental photographic album printed by famed Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner from negatives by an itinerant American photographer, Henry De Witt Moulton. Moulton’s photos of Lima and the Chincha Islands...

Monumental photographic album printed by famed Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner from negatives by an itinerant American photographer, Henry De Witt Moulton. Moulton’s photos of Lima and the Chincha Islands were taken while he was living in Peru, sometime between 1860 and mid-1863, when he returned to the US. The size of the edition is unknown, and despite being printed around the same time as Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (and advertised with it in early 1866), copies are exceedingly rare.

The album’s significance is often underestimated. Gardener’s selection of 38 (36 in the present copy) views of Lima and Callao largely follow the format of contemporary images of the capital’s major monuments. The extraordinary nature of the album lies instead in Gardner’s addition of 32 of Moulton’s unique “views of those celebrated Islands situated within the rainless region of the Peruvian Coast, and which furnish the richest fertilizing material known to agriculture.”*

In the early 1860s the Chincha Islands’ guano heaps were the world’s most important source of fertilizer. Revenues from the nationalized deposits paid for much of Peru’s public works from 1840-1870, including construction of the railways that crossed the Andes. Even more importantly, guano income was used by the state to free its black slaves and to abolish poll taxes on indigenous citizens.

Despite these progressive measures, the Chincha Islands’ guano piles were worked by prisoners and indentured Chinese laborers who were imported to replace freed slaves. Moulton’s “most interesting images concerned the soon to be depleted guano itself and the process used to exploit it.” His dramatic photos include images of the “Great Heap” with workmen loading rail cars, others of craft transporting the cargo to ships, and piers, and poignant images of the laborers who Moulton seems to have seen as victims of exploitation. A small church for the workers appears three times; in one the prisoner-laborers are surrounded by armed soldiers while they kneel outside during Sunday services. Gardner’s rich contact prints preserve these minute details and the subtle value transitions of Moulton’s negatives.

In April 1864, just before Gardner assembled the album, the Chincha Islands became an object of great concern for the US when Spain seized them “as part of European efforts to re-establish colonial rule in South America while the United States was preoccupied with its Civil War.” He foresaw the historical value of the work when he wrote in his preface “In after times, these sketches of the Chincha Islands will have a peculiar interest [...] The original estimate of the length of time—one thousand years—that this deposit of the Chincha Islands would suffice for the wants of the world, is destined to prove fallacious. So great has become the demand for it that half the deposit of the largest island has been removed already; and the probabilities are, that in twenty years the supply will be exhausted.”

Four copies are recorded in three public collections: the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, and the Public Library of Cincinnati. Two have come to auction in the last 35 years. The most recent, a complete copy offered at Swann, sold for $35,000.

The album’s significance is often underestimated. Gardener’s selection of 38 (36 in the present copy) views of Lima and Callao largely follow the format of contemporary images of the capital’s major monuments. The extraordinary nature of the album lies instead in Gardner’s addition of 32 of Moulton’s unique “views of those celebrated Islands situated within the rainless region of the Peruvian Coast, and which furnish the richest fertilizing material known to agriculture.”*

In the early 1860s the Chincha Islands’ guano heaps were the world’s most important source of fertilizer. Revenues from the nationalized deposits paid for much of Peru’s public works from 1840-1870, including construction of the railways that crossed the Andes. Even more importantly, guano income was used by the state to free its black slaves and to abolish poll taxes on indigenous citizens.

Despite these progressive measures, the Chincha Islands’ guano piles were worked by prisoners and indentured Chinese laborers who were imported to replace freed slaves. Moulton’s “most interesting images concerned the soon to be depleted guano itself and the process used to exploit it.” His dramatic photos include images of the “Great Heap” with workmen loading rail cars, others of craft transporting the cargo to ships, and piers, and poignant images of the laborers who Moulton seems to have seen as victims of exploitation. A small church for the workers appears three times; in one the prisoner-laborers are surrounded by armed soldiers while they kneel outside during Sunday services. Gardner’s rich contact prints preserve these minute details and the subtle value transitions of Moulton’s negatives.

In April 1864, just before Gardner assembled the album, the Chincha Islands became an object of great concern for the US when Spain seized them “as part of European efforts to re-establish colonial rule in South America while the United States was preoccupied with its Civil War.” He foresaw the historical value of the work when he wrote in his preface “In after times, these sketches of the Chincha Islands will have a peculiar interest [...] The original estimate of the length of time—one thousand years—that this deposit of the Chincha Islands would suffice for the wants of the world, is destined to prove fallacious. So great has become the demand for it that half the deposit of the largest island has been removed already; and the probabilities are, that in twenty years the supply will be exhausted.”

Four copies are recorded in three public collections: the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, and the Public Library of Cincinnati. Two have come to auction in the last 35 years. The most recent, a complete copy offered at Swann, sold for $35,000.