Wilkins Photo Service

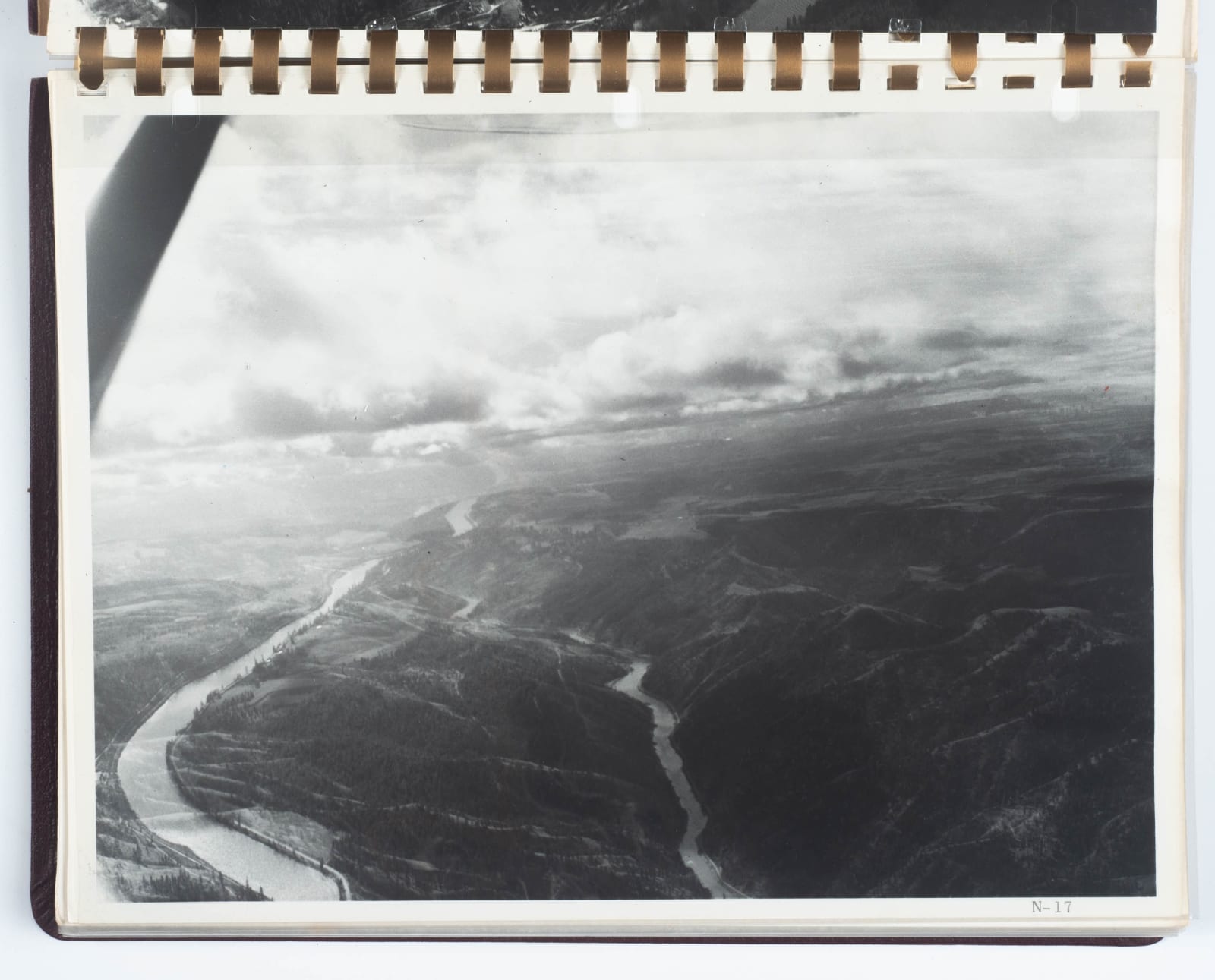

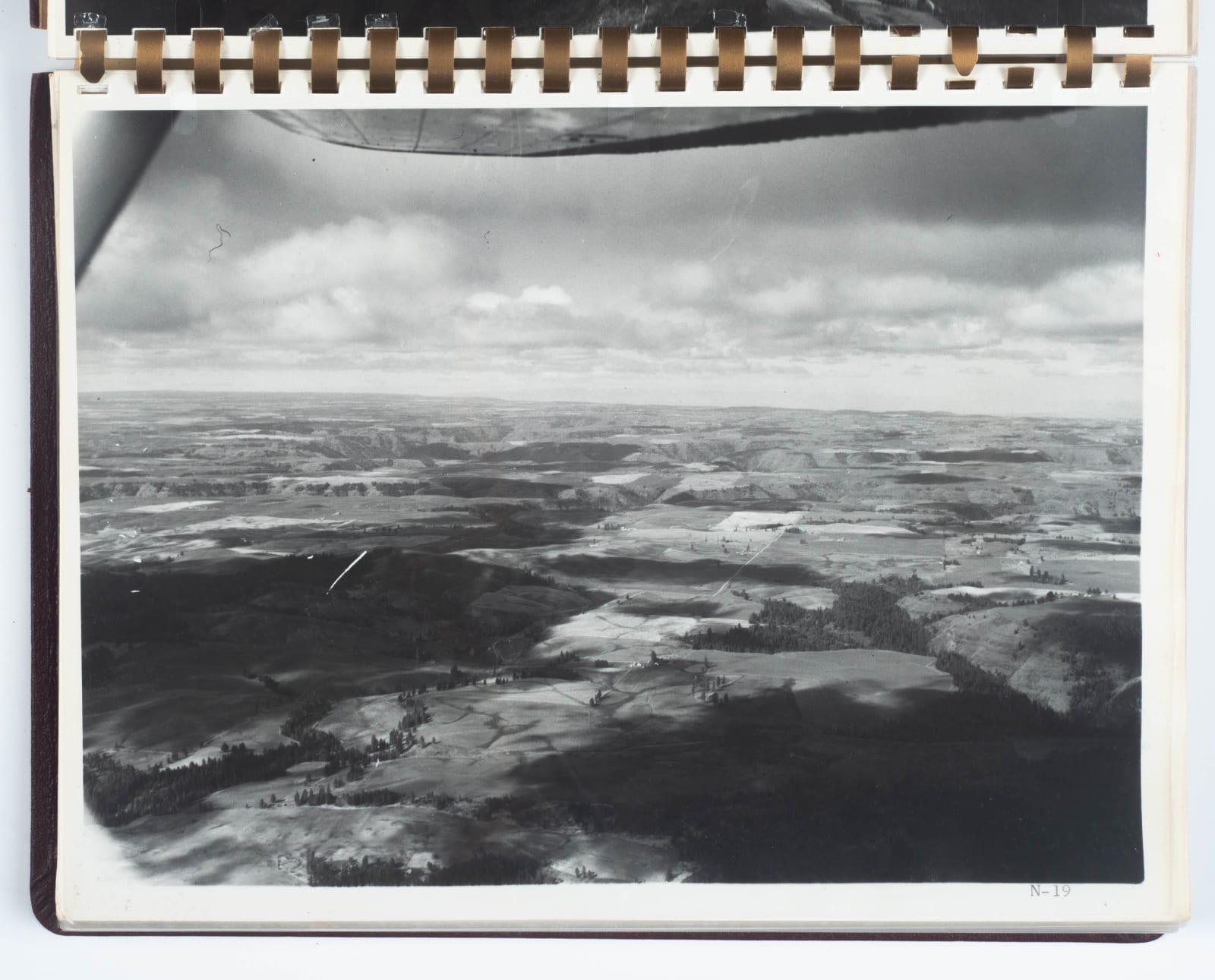

Aerial Photos of Nez Perce Tribal Lands Presented to the Indian Claims Commission, 1954-56

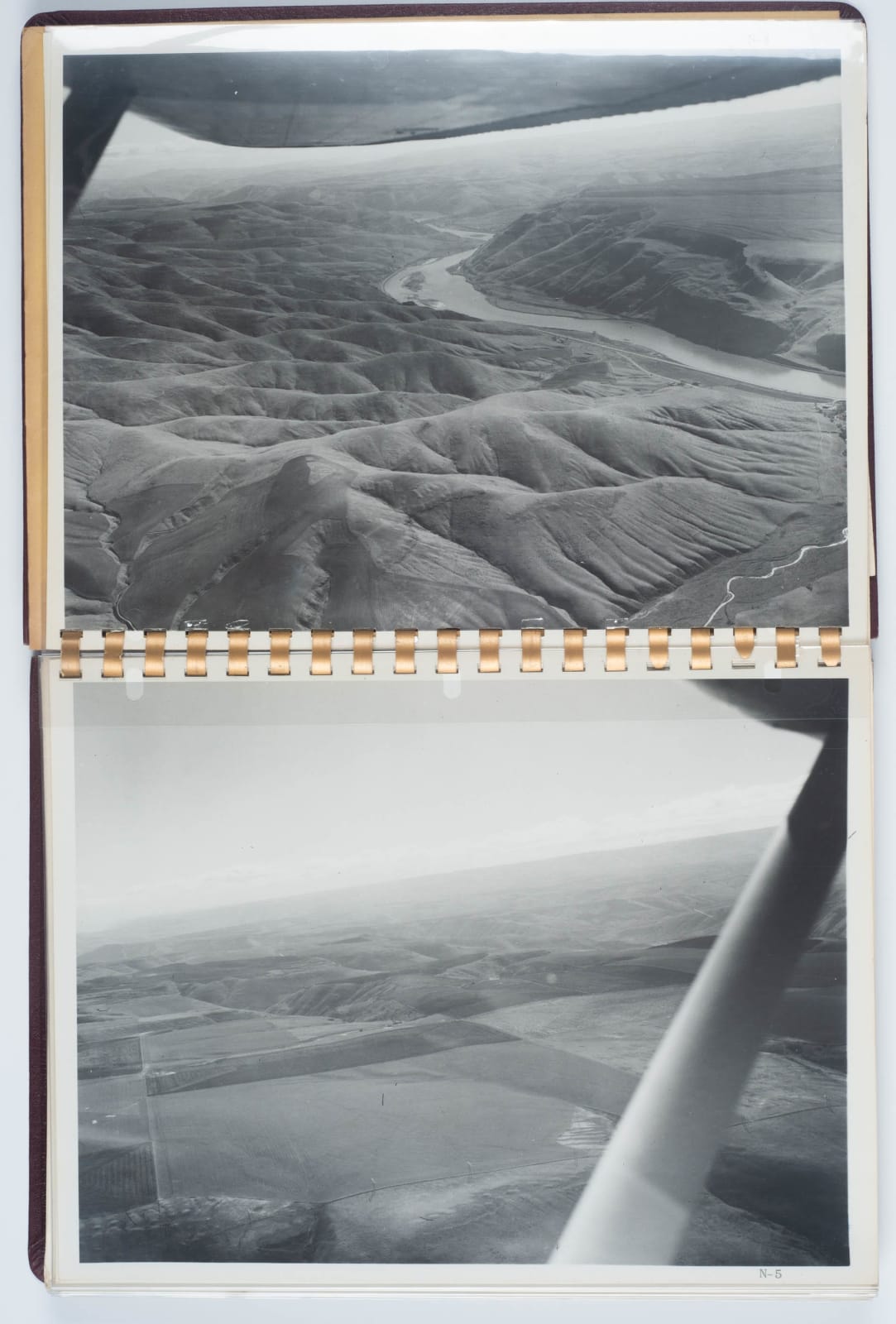

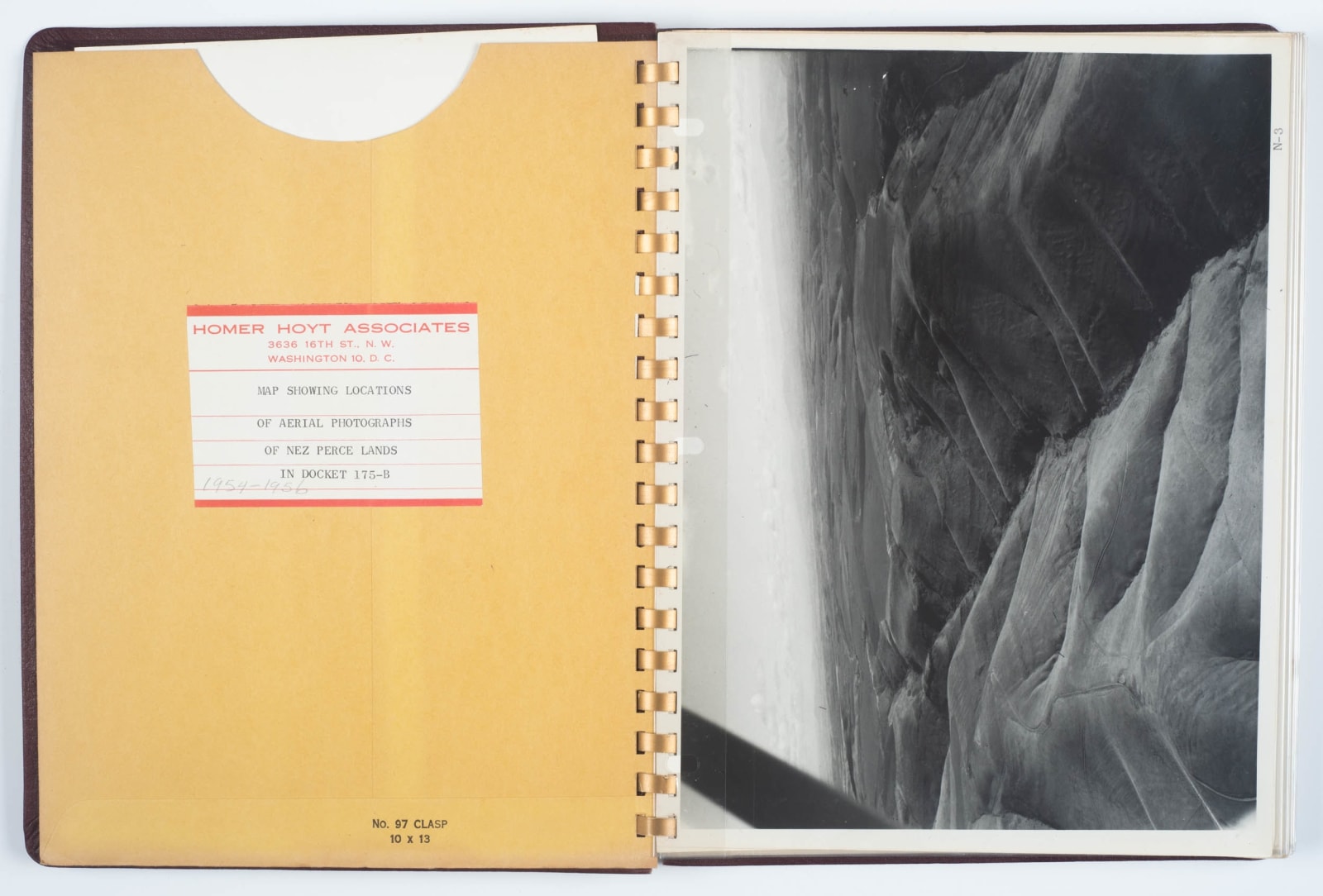

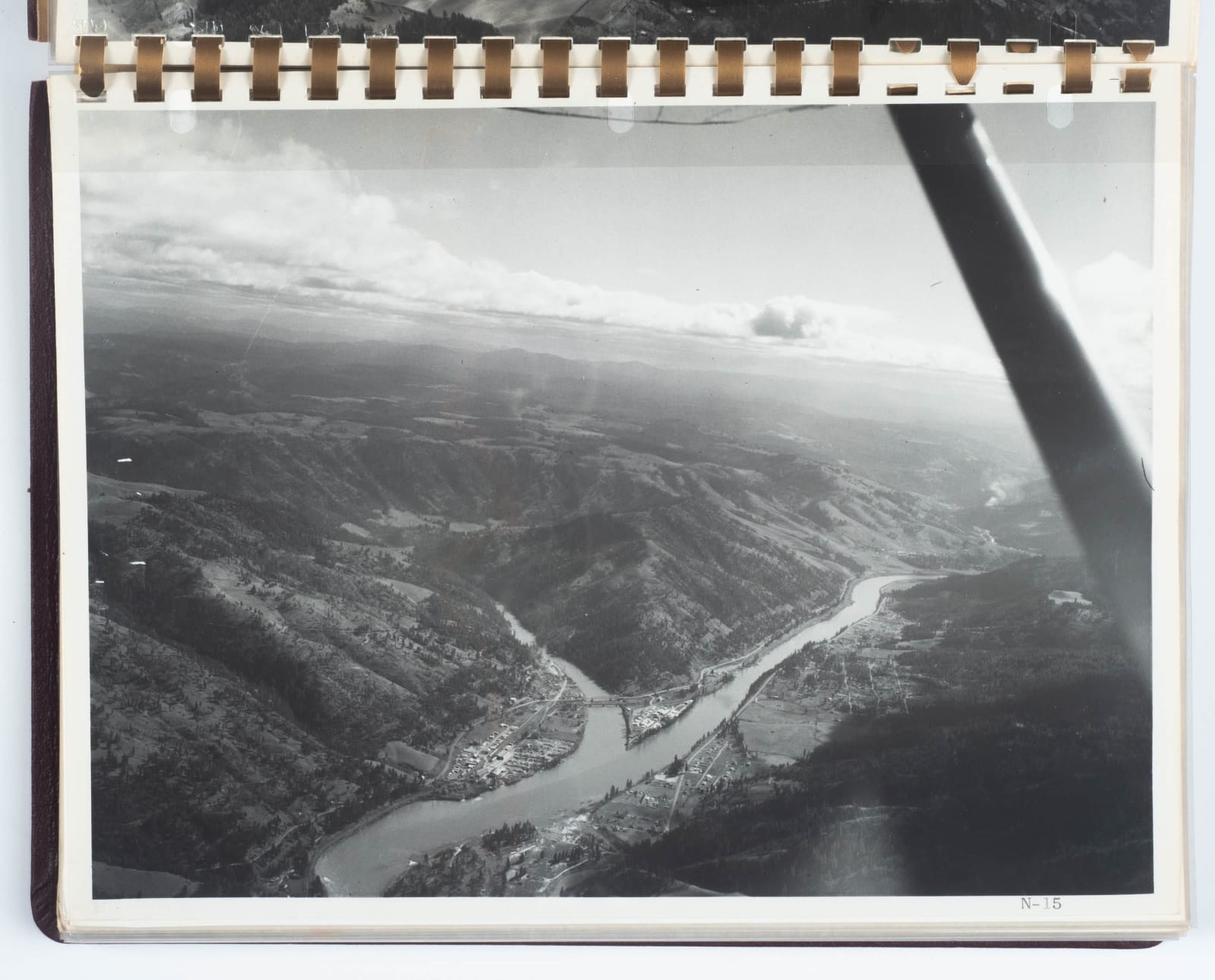

Photo album; silver prints (47)

Each 8 x 10 inches

Some with photographer's credit stamp verso

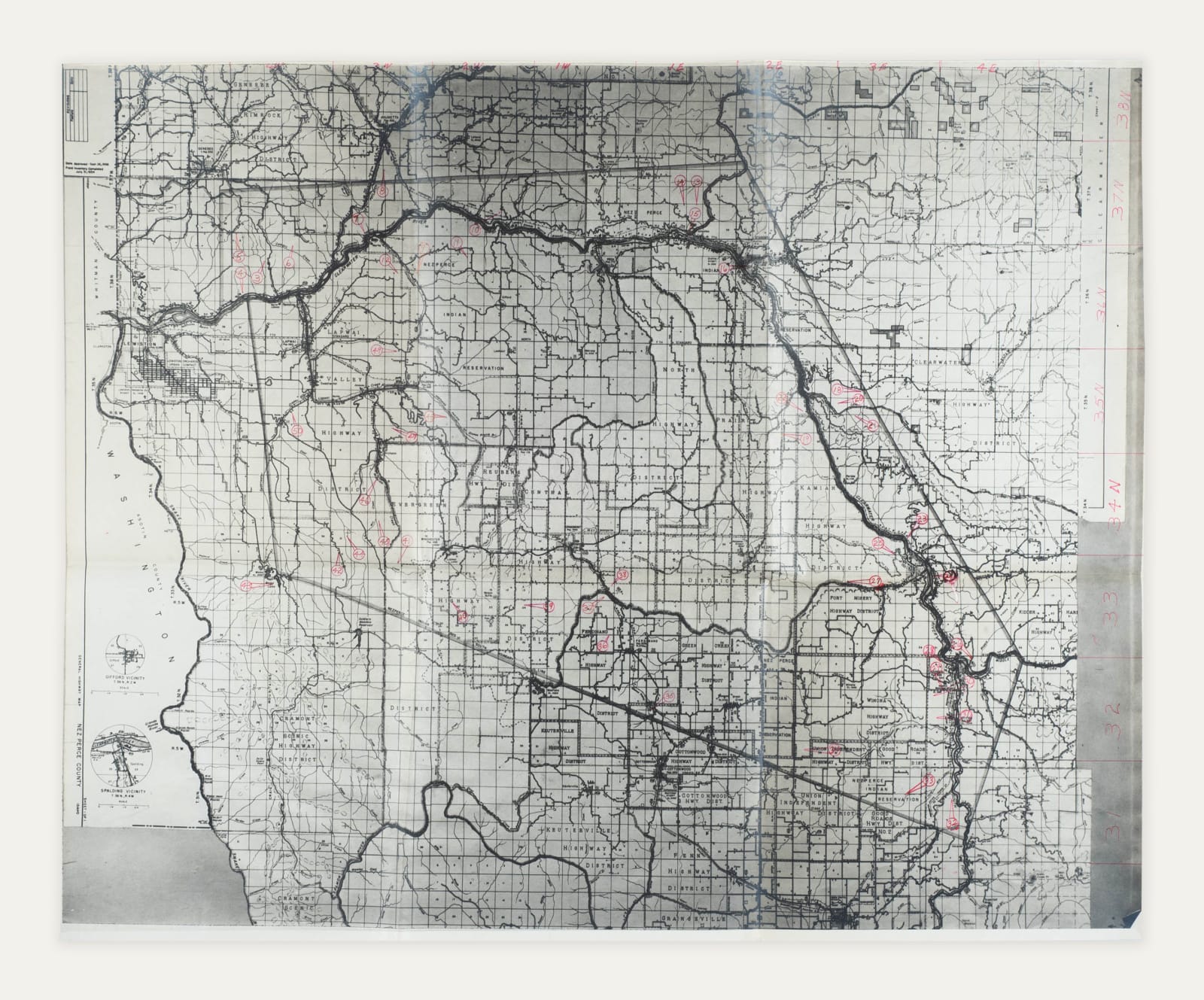

Album contains a folder with large photographically-reproduced map.

Some with photographer's credit stamp verso

Album contains a folder with large photographically-reproduced map.

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

This spiral-bound album of aerial photographs speaks to the varied, often complicated uses of photography. The images were taken by the Wilkins Photo Service of Lewiston, Idaho and used by...

This spiral-bound album of aerial photographs speaks to the varied, often complicated uses of photography. The images were taken by the Wilkins Photo Service of Lewiston, Idaho and used by Homer Hoyt Associates as evidence in the Indian Claims Commission case, “Nez Perce Indian Tribe V. United States.”

The Indian Claims Commission was formed as part of the Indian Claims Act of 1946. It was an independent judicial relations arbiter established to hear longstanding tribal claims against the US Government. As stated by the Department of Indian Affairs, the claims represented “attempts by Indian tribes to obtain redress for any failure of the Government to complete payments for lands ceded under treaty, for the acquisition of land at an unconscionably low price or for other failure to comply with a treaty or legislative action regarding Indian lands that grew out of the westward expansion of the United States.”

Among the claims the Nez Perce brought to the commission, one was that they were owed additional compensation for the reservation lands which it ceded to the United States by the Agreement of May 1,1893. The agreement involved sending a surveyor to determine and assign parcels to individual tribal members, then declaring the remaining reservation area open for non-Indian settlement. The parcels not assigned to tribal members were sold to the Government at $2.97 an acre. These neighboring tribal and non-tribal parcels of land, called a “checkerboard reservation,” is reflected in the photographically-produced map which accompanies the aerial photos.

The Nez Perce brought in appraiser William C. Brown to value the land, and the US Government brought in Homer Hoyt, a real estate economist best known for his sector theory on urban land use. Hoyt was the Chief Land Economist for the Federal Housing Authority in the 1930s, and during his tenure there he developed the racist policy of redlining, arguing that racially-mixed neighborhoods decreased property value.

To determine a number for the Nez Perce lands, Both Hoyt and Brown looked at comparable sales, as well the topography, soil conditions, transportation availability and other factors to reach a conclusion. Brown valued the land at 11.89 per acre, and Hoyt came in at 1.29 per acre. The commission concluded the value to be around 4 dollars per acre and therefore did not meet the threshold of “unconscionably low,” though they did note that Hoyt’s figure was “overly pessimistic” and that he “over-discounted the value of the lands.” The Nez Perce unsuccessfully appealed the decision.

Folder bears a stamp with Indian Claims Commission information and another reading "Surplus - 3 / Library of Congress / Duplicate."

The Indian Claims Commission was formed as part of the Indian Claims Act of 1946. It was an independent judicial relations arbiter established to hear longstanding tribal claims against the US Government. As stated by the Department of Indian Affairs, the claims represented “attempts by Indian tribes to obtain redress for any failure of the Government to complete payments for lands ceded under treaty, for the acquisition of land at an unconscionably low price or for other failure to comply with a treaty or legislative action regarding Indian lands that grew out of the westward expansion of the United States.”

Among the claims the Nez Perce brought to the commission, one was that they were owed additional compensation for the reservation lands which it ceded to the United States by the Agreement of May 1,1893. The agreement involved sending a surveyor to determine and assign parcels to individual tribal members, then declaring the remaining reservation area open for non-Indian settlement. The parcels not assigned to tribal members were sold to the Government at $2.97 an acre. These neighboring tribal and non-tribal parcels of land, called a “checkerboard reservation,” is reflected in the photographically-produced map which accompanies the aerial photos.

The Nez Perce brought in appraiser William C. Brown to value the land, and the US Government brought in Homer Hoyt, a real estate economist best known for his sector theory on urban land use. Hoyt was the Chief Land Economist for the Federal Housing Authority in the 1930s, and during his tenure there he developed the racist policy of redlining, arguing that racially-mixed neighborhoods decreased property value.

To determine a number for the Nez Perce lands, Both Hoyt and Brown looked at comparable sales, as well the topography, soil conditions, transportation availability and other factors to reach a conclusion. Brown valued the land at 11.89 per acre, and Hoyt came in at 1.29 per acre. The commission concluded the value to be around 4 dollars per acre and therefore did not meet the threshold of “unconscionably low,” though they did note that Hoyt’s figure was “overly pessimistic” and that he “over-discounted the value of the lands.” The Nez Perce unsuccessfully appealed the decision.

Folder bears a stamp with Indian Claims Commission information and another reading "Surplus - 3 / Library of Congress / Duplicate."