Marion Palfi

32 Photos from "First I Like the Whites..." a Study on Native American Life, 1967-69

Silver prints (32); printed 1970s

Each approximately 10 x 13 1/2 inches; mounts 16 x 20

Each with photographer's signature mount recto and date, caption and notations mount verso.

Each with photographer's signature mount recto and date, caption and notations mount verso.

Sold

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

In 1967, on a Guggenheim Fellowship, the social-documentary photographer Marion Palfi spent two years living intermittently with a family on the Hopi reservation in Northern Arizona. Palfi, had spent her...

In 1967, on a Guggenheim Fellowship, the social-documentary photographer Marion Palfi spent two years living intermittently with a family on the Hopi reservation in Northern Arizona. Palfi, had spent her career documenting social injustices and marginalized communities with powerful photo essays and photo books such as 1949’s “There is No More Time: An American Tragedy,” which documented racism and segregation in Georgia, and 1952’s “Suffer the Little Children,” which focused on the living conditions of impoverished children. With this project, she sought to turn her camera toward the Native American experience in the United States.

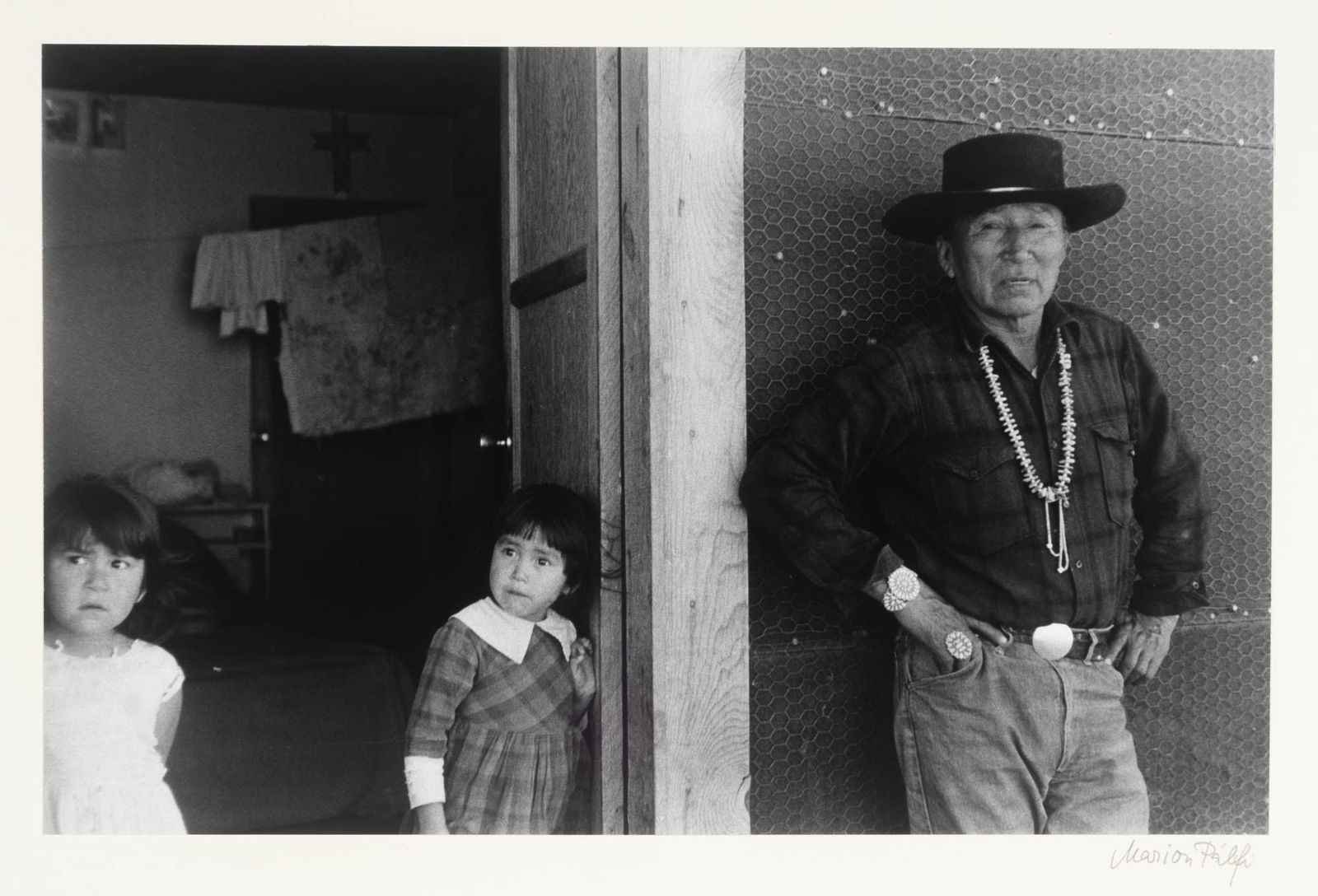

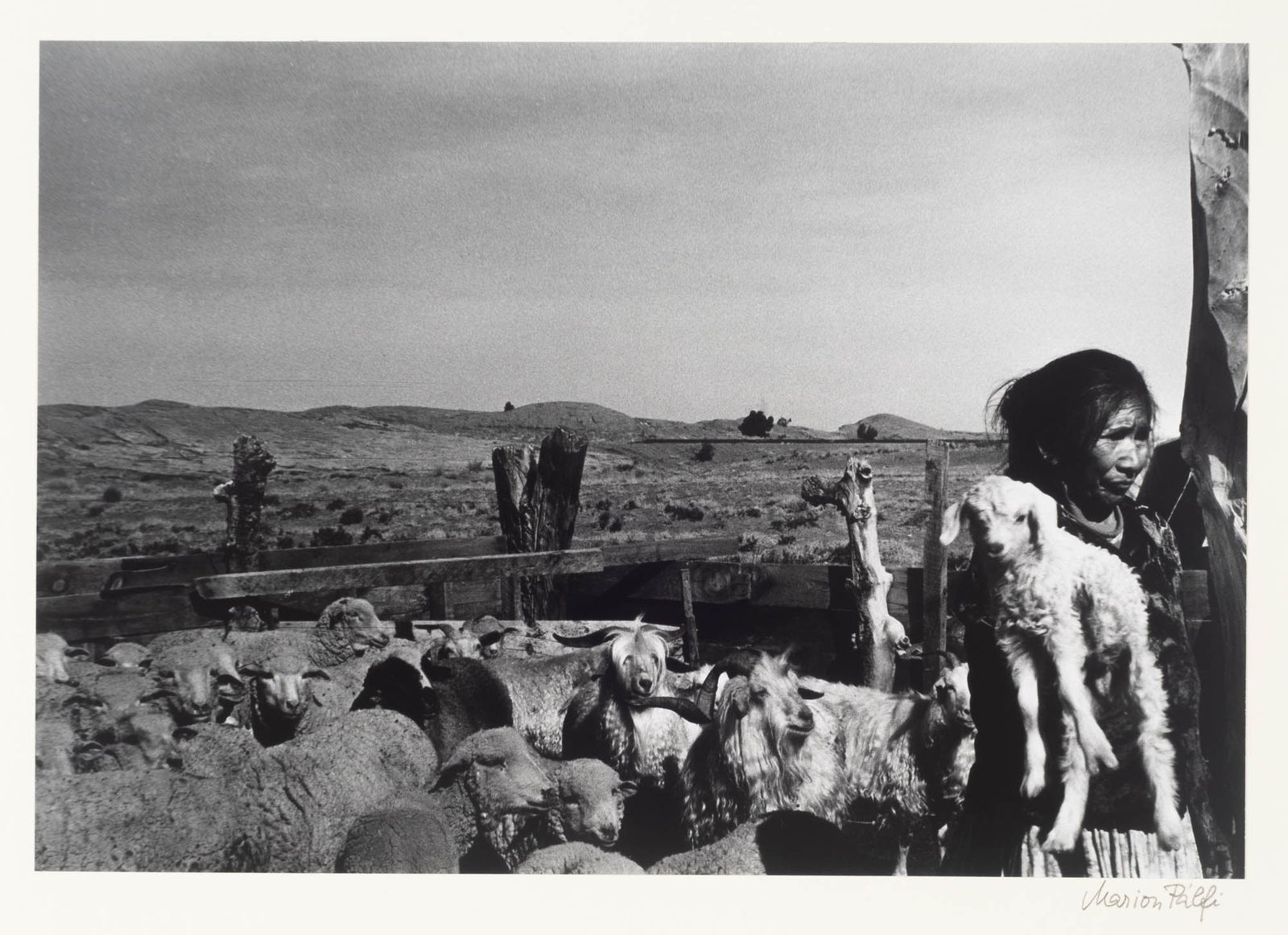

Her aim was to create a two-part photographic study. The first showing the daily lives and cultures of the Hopi, Navajo and Papago (Tohono O’odham) tribes, and the second exploring the effects of government programs geared toward Native American “acculturation” and “relocation.” Palfi intended to create a book of this work, titled “My Children, First I Like the Whites, I Gave Them Fruit.” The project was unfinished at the time of her death in 1978, but some of her photographs from this project appeared in her 1973 exhibition “Invisible in America” at the University of Kansas.

The present collection includes 32 photographs from this series, printed by Palfi in the early 1970s for a retrospective at the Witkin Gallery. The photos are each mounted, with captions on the verso in the artist’s hand. There are eight photographs in the “Papagoland” series, six in the “Najavoland,” and seven in the “Hopiland” series. The Papagoland group includes a number of sensitive portraits of the noted potter Laura Kerman, one beautiful image from “Navajoland” shows a group of women practicing traditional weaving, and a highlight of the “Hopiland” photographs is one titled “Self-government;” a seemingly-straightforward yet layered, complex study of a tribal council meeting.

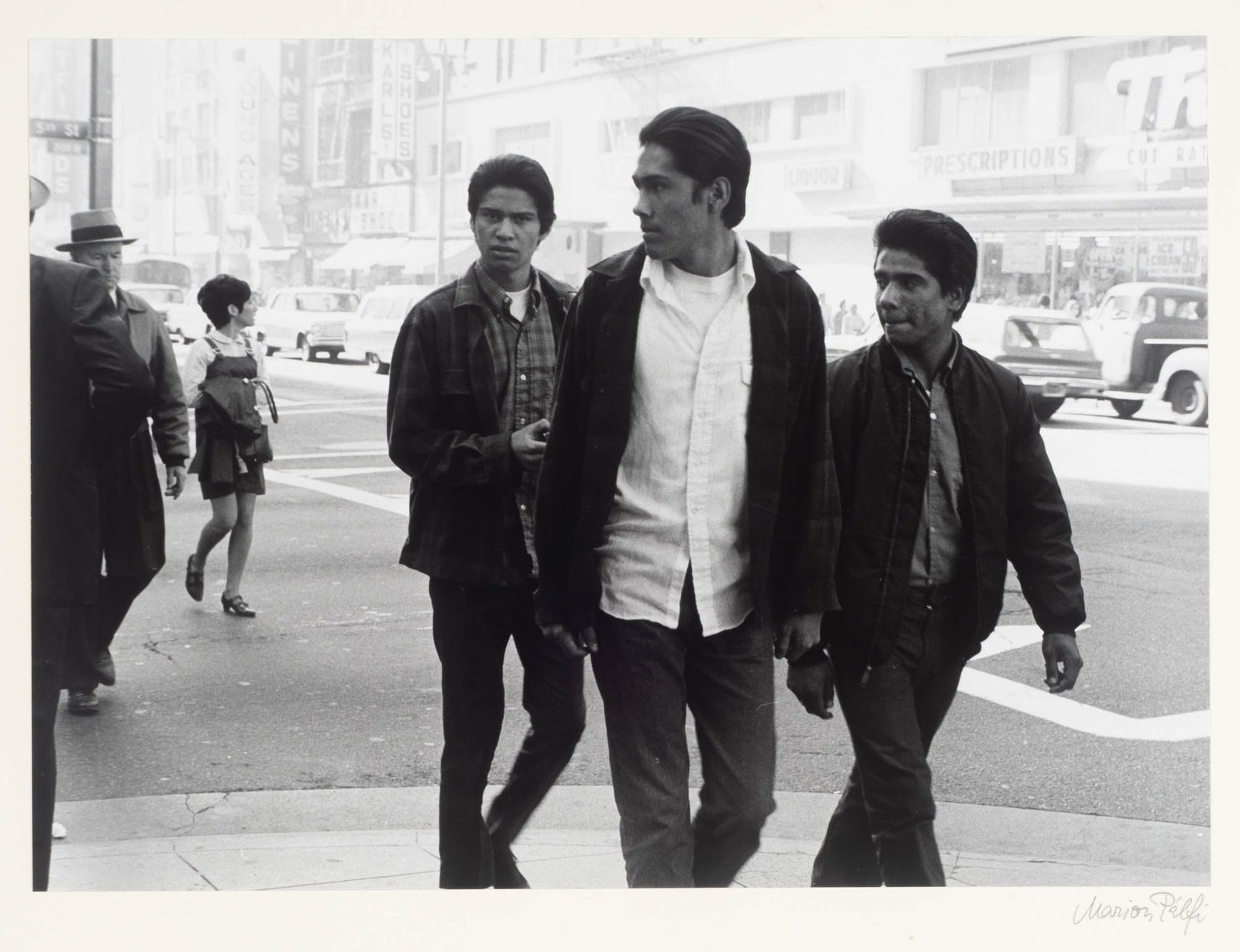

The other twelve photographs, all from the “Relocation” portion of the project, are perhaps the most powerful. One image which is captioned, “New arrival from Apacheland at ‘Relocation School,’ Madera, California” shows a young Native American woman in Western clothes, with a Western hairstyle, an anxious expression on her face, frozen in front of an imposing, seemingly endless stretch of lockers. By contrast, some photographs are less overt in their meaning, such as two photographs showing life for young Native Americans in Los Angeles. One of these presents three young men in stylish garb and slicked back hair, walking down a busy LA street, and another shows a woman shopping at an appliance store.

Born in Berlin, Germany in 1907, Marion Palfi began her artistic career as a dancer, model actress. Her love of photography began when she was given a small camera by a friend, which led her to apprentice at a commercial portrait studio in Berlin, eventually opening her own portrait gallery in 1934. She fled the country in 1940 and found work at a photo-finishing and processing firm in Los Angeles.

Her first professional break came in 1945 when she was commissioned by the Council Against Intolerance in America to study minority artists. This led to her first solo exhibition, "Great American Artists of Minority Groups and Democracy at work," at the Norlyst Gallery in New York. Palfi received several awards, including the Ministry of Education Award and Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1945 and 1946 respectively. She used the money from the Rosenwald Fellowship to travel the United States, documenting racism and discrimination with an unflinching, deeply-sympathetic eye.

In 1955, her work was included in Edward Steichen's seminal "Family of Man" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She spent the 960s continuing to fight for Civil Rights, both as an activist and photographer. She received a National Endowment for the Arts Photography Fellowship in 1974 and taught Photographic Social Research at the Inner City Institute in Los Angeles from 1971 until her death in 1978. In July of 2021, the Phoenix Art Museum held a major retrospective of her work, “Freedom Must Be Lived: 1940-1978.”

Her aim was to create a two-part photographic study. The first showing the daily lives and cultures of the Hopi, Navajo and Papago (Tohono O’odham) tribes, and the second exploring the effects of government programs geared toward Native American “acculturation” and “relocation.” Palfi intended to create a book of this work, titled “My Children, First I Like the Whites, I Gave Them Fruit.” The project was unfinished at the time of her death in 1978, but some of her photographs from this project appeared in her 1973 exhibition “Invisible in America” at the University of Kansas.

The present collection includes 32 photographs from this series, printed by Palfi in the early 1970s for a retrospective at the Witkin Gallery. The photos are each mounted, with captions on the verso in the artist’s hand. There are eight photographs in the “Papagoland” series, six in the “Najavoland,” and seven in the “Hopiland” series. The Papagoland group includes a number of sensitive portraits of the noted potter Laura Kerman, one beautiful image from “Navajoland” shows a group of women practicing traditional weaving, and a highlight of the “Hopiland” photographs is one titled “Self-government;” a seemingly-straightforward yet layered, complex study of a tribal council meeting.

The other twelve photographs, all from the “Relocation” portion of the project, are perhaps the most powerful. One image which is captioned, “New arrival from Apacheland at ‘Relocation School,’ Madera, California” shows a young Native American woman in Western clothes, with a Western hairstyle, an anxious expression on her face, frozen in front of an imposing, seemingly endless stretch of lockers. By contrast, some photographs are less overt in their meaning, such as two photographs showing life for young Native Americans in Los Angeles. One of these presents three young men in stylish garb and slicked back hair, walking down a busy LA street, and another shows a woman shopping at an appliance store.

Born in Berlin, Germany in 1907, Marion Palfi began her artistic career as a dancer, model actress. Her love of photography began when she was given a small camera by a friend, which led her to apprentice at a commercial portrait studio in Berlin, eventually opening her own portrait gallery in 1934. She fled the country in 1940 and found work at a photo-finishing and processing firm in Los Angeles.

Her first professional break came in 1945 when she was commissioned by the Council Against Intolerance in America to study minority artists. This led to her first solo exhibition, "Great American Artists of Minority Groups and Democracy at work," at the Norlyst Gallery in New York. Palfi received several awards, including the Ministry of Education Award and Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1945 and 1946 respectively. She used the money from the Rosenwald Fellowship to travel the United States, documenting racism and discrimination with an unflinching, deeply-sympathetic eye.

In 1955, her work was included in Edward Steichen's seminal "Family of Man" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She spent the 960s continuing to fight for Civil Rights, both as an activist and photographer. She received a National Endowment for the Arts Photography Fellowship in 1974 and taught Photographic Social Research at the Inner City Institute in Los Angeles from 1971 until her death in 1978. In July of 2021, the Phoenix Art Museum held a major retrospective of her work, “Freedom Must Be Lived: 1940-1978.”